How to manage mental health: the music industry’s new priority

This year’s Mental Health Awareness Week has placed a special focus on relationships. Here Fiona McGugan, general manager of the Music Manager’s Forum, reports on the increasingly vital role of the emotionally responsible manager in the industry.

Life in the music industry is likely to take its toll on a person regardless of mental vulnerability. Being thrust into the spotlight can be difficult enough – never mind the added pressures of completing a busy promo circuit or travelling the world on a non-stop tour – but it can also expose or create much deeper problems.

During Mental Health Awareness Week this year, from 16 to 22 May, the Mental Health Foundation has placed a special focus on relationships. “We believe we urgently need a greater focus on the quality of our relationships,” says the charity. “We need to understand just how fundamental relationships are to our health and wellbeing. We cannot flourish as individuals and communities without them. In fact, they are as vital as better-established lifestyle factors, such as eating well, exercising more and stopping smoking.”

In the music industry, there should arguably be no greater working relationship than that between an artist and their manager. Far from the cliche of a cigar-chomping penny counter, a good modern music manager will protect their client’s emotional, mental and physical state just as passionately as their business interests. It’s a role that can make all the difference for artists who may be struggling with the demands of stardom, along with any other mental health challenges they harbour.

“If there’s one thing that’s for sure, it’s that success and adulation never made any human being any more normal,” says Marc Marot, a former UK record label boss and chairman of Crown Talent Management, which has the likes of Ella Henderson, Becky Hill and Jay McGuiness on its music roster. “What we’re trying to do for our artists on a daily basis is make them more extraordinary. So we’re setting people up to have a different way of thinking to the rest of humanity. Then we wonder why they think differently!”

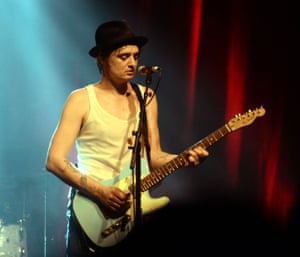

Recently, there has been an increased awareness of mental health in the creative industries. The stigma surrounding mental illness appears to be fading, if slightly: last year, prominent music stars such as Pete Doherty and Florence Welch talked openly about their own battles with anxiety and depression. Meanwhile, the death of Amy Winehouse in 2011 has forced more discussion around mental health, addiction and adequate care across the music industry.

-

Battles with depression … Pete Doherty. Photograph: Anita Russo/Rex/Shutterstock

“I think it’s come to the fore more recently,” says David Enthoven, a veteran of the business and co-founder of management company ie:music, which looks after big names including Robbie Williams, Will Young, Passenger, Lemar and Ladyhawke. “When I came in, nobody had heard of anything like Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous. It was around, but you just didn’t talk about it, and a lot of artists died young in the 60s because of a drug overdose or too much alcohol. I think it was almost seen as a badge of honour to get up on stage and be completely wrecked.”

The demands on modern-day musicians are far greater than they were in those days, he adds. “There weren’t camera phones back then, so you couldn’t be caught in unguarded moments. Things have definitely changed and your faults are magnified and spread.”

Enthoven is particularly well qualified when it comes to looking after artists struggling with addiction. Now in his 70s, he himself had a serious drug problem 30 years ago. But rather than try to bury his experiences, he is ultimately able to draw on them to help troubled artists.

“If anybody asks, I’ll immediately offer to help,” he says. “I think artists are more susceptible to having issues – whether its mental issues or drug-related. Much of it is to do with self-esteem and fear. Most of the artists I work with are sensitive in certain areas, they have heightened awareness, heightened sensitivity, and a lot of them do have low self-esteem. That’s interesting because they go out, become somebody else and perform. I think they are very brave. I have one artist who is almost physically sick before going out on stage but she is so determined and wants to do what she is doing so much that she pushes through that fear.”

If the demands of being a prominent musician are greater than ever, and management companies are shouldering an increasing responsibility for their clients’ overall wellbeing and career, then it is often the manager who is the first responder if mental health deteriorates. But, as multiskilled as they need to be in 2016, managers are not qualified therapists. So how do they handle complex mental illnesses if they begin to emerge? For Ellie Giles,, who looks after Bill Ryder-Jones, the most important thing is simply to lend an ear.

“All you need to do is listen and work out what help they need,” she says. “Great managers in any industry are there to work out what an artist or person needs and then mentor, support and advise them. Ultimately that’s what management is: it’s enabling and empowering that person.

“Bill Ryder-Jones has a dissociative disorder,” she offers as an example. “When he gets into a bad place, he ends up unable to see himself in the mirror and feels that he’s part of a computer game, which is something that I’d never come across before I managed him. The only way that you can manage something like that is by listening.

-

Dissociative disorder… Bill Ryder-Jones. Photograph: Rachel King

“When it comes to managing people with mental-health issues, it’s all about working out where their head is at. Are they actually in the middle of an episode or not? It can be a hard judgment to make but it’s ultimately the only thing you can do. Then it’s about finding help.”

For Crown’s Marot, that final step is crucial. Just as a suffering artist needs the support of their manager, the manager themselves must rally the wider team to bolster that support before seeking out professional help where necessary.

“The problem for many young managers is they’re on their own, so they don’t have resources around them,” says Marot. “Perhaps your artist has got a major record deal but, because the manager is young and inexperienced, they don’t know how to reach out to people or they think that doing so is a sign of weakness when it isn’t.

“It’s got to be confronted as early as possible,” he adds. “The Amy Winehouse lyric about not wanting to go to rehab was aimed at a manager, legend has it, but you can’t be put off having that confrontational conversation early and trying to break the pattern of self-harm, stress, or whatever it is by seeking professional help quickly rather than trying to cope on your own.”

Although artists and managers seem increasingly able to face these battles, there is a consensus that more needs to be done across the music business as a whole.

One website, MusicSupport.org, appears to be a big step in the right direction. A non-profit collective providing confidential help and support for individuals across the UK music business, it is driven by industry figures such as Squeeze’s Chris Difford, artist manager Matt Thomas, session musician Rachael Lander, tour manager Andy Franks and drummer Mark Richardson, along with clinical director Johan Sorensen.

Meanwhile, at the Music Managers Forum, we’re researching the potential for a range of resources that will help young and established managers dealing with mental illness and addiction – whether it’s their clients who are affected or anyone else on the large teams many artists require to help drive success.

As MMF co-chair Diane Wagg explains: “We looked at all the training that we do for managers. The thing that seemed to be missing was that we weren’t teaching our membership what to do when a client is having real problems – a nervous breakdown, relationship problems on tour, writers’ block, panic attacks on stage … It’s one area that we’re really developing in terms of modules and resources.

“It’s not just about dealing with problems when they arise – and we do need to develop some really great support systems for that – but also educating people so they are able to spot the signs. When does it go from someone feeling down to being really depressed, for example?

“There are a number of things we can do. We are developing courses and modules about what to look out for and how to deal with them. We’re also getting a lot of calls into MMF HQ from managers asking when they should take action. I think by talking more openly about it, we’ll develop better forums where we share experiences.

-

Rumer: ‘We talk a lot about sustainability; remember that an artist’s health is at the core of that.’ Photograph: Katherine Anne Rose for the Observer

“And we have to remember that it’s not just artists who are susceptible to mental health problems,” adds Wagg. “The fact that artists increasingly feel able to talk and be open about problems is fantastic and is encouraging discussion and development of much better support systems, but people on the management, business and tour sides have generally felt less able to share their problems, feeling they may lose clients if they do. We hope we’re building a world where everyone will feel supported.”

Having released three studio albums on major labels between 2010 and 2014 and been nominated for two Brit awards in 2011, Rumer, who is also a board director at the Featured Artists Coalition, has witnessed the success that the business can bring but also the damage it can do.

“Maintaining an artist’s health is in the best interest of everyone – the label and the management as well as the artist themselves,” she says. “For that reason, there needs to be more investment in acts’ wellbeing: making sure the schedule is reasonable, hiring a good PA, getting the best doctors, making sure they have access to counselling even on the road. We talk a lot about sustainability; remember that an artist’s health is at the core of that.”

For mental health problems in the UK, the Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123, or visit Mind’s website. In the US, if you are in crisis or need someone to talk to, call the Samaritans branch in your area or 1 (800) 273-TALK. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is on 13 11 14. Hotlines in other countries can be found here.

This article was originally published by The Guardian.